A Word from the Presence

Under the Broom Tree — Lessons From Elijah the Tishbite

“In an age of darkness and compromise, Elijah remains the symbol of unyielding loyalty to God.” — Abraham Heschel

This series, “Under the Broom Tree,” is a journey through the life of Elijah, a prophet who stood boldly on mountaintops and despaired under a broom tree. His story is not one of unshakable confidence, but of faith that was tested by fear, loneliness, and distress.

We live in an age not unlike Elijah’s: an age of drift, moral confusion, and spiritual fatigue. He shows us what it means to stand before God, even when everything else is crumbling. He teaches us how to be bothered in the right way — and how to remain faithful when we feel like we’re the only ones left.

Link to previous article: [Post 1]

The Madness of the Messenger

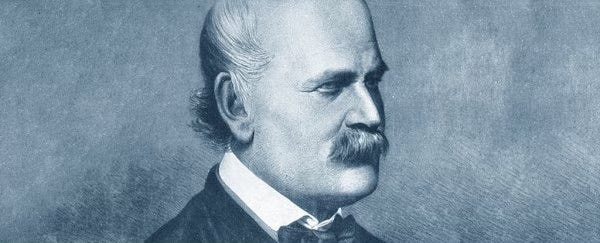

In 1847, a Hungarian obstetrician named Ignaz Semmelweis noticed something alarming. In his hospital, far more women were dying in the doctor-run maternity ward than in the one run by midwives.

He studied, hypothesized, compared, and observed until he discovered that the cause might be something as simple as what we do before eating or after using the restroom. The doctors weren’t washing their hands! They performed autopsies and went straight to the delivery room, hands soaked with the chemicals from the earlier work.

He instituted a rule that seemed absurd at the time — wash with chlorinated lime before seeing patients. As this new practice began, death rates plummeted and lives were saved.

But rather than gratitude, Semmelweis received ridicule. His findings were dismissed by his colleagues due to his eccentric and erratic behavior. His insistence on this practice was called mania. Eventually, he was institutionalized, beaten by guards in an asylum, where he died alone.

Years later, Louis Pasteur’s work on germ theory and Joseph Lister’s pioneering use of antiseptics would vindicate Semmelweis, confirming that invisible microorganisms cause infection and that handwashing drastically reduces their spread. But in the meantime, many lives were lost — all because the messenger seemed a bit off.

It makes you wonder if that’s what happened in Ahab’s court when Elijah said, “As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word” (1 Kings 17:1).

Three years later, Elijah would be the object of a nationwide manhunt (1 Kings 18:10). Why search for a man you consider to be a danger to society, when he is right there in front of you?

The answer can only be that when he made his pronouncement, he wasn’t believed, wasn’t taken seriously.

My father once told me about a day in Nigeria. He was handing out gospel tracts on a dusty roadside when a Mercedes slowed beside him. He offered the driver one through the passenger-side window. The man quickly assessed his appearance — worn sandals, tattered trousers, sweat-stained shirt — then he handed the tract back and said, “I think you need Jesus more than I do.”

Sometimes it is the messenger that determines whether or how the message is received.

No doubt, this was the case when Elijah came to give Ahab the weather report. He wandered in, wrapped in obscurity. An untamed, unimpressive, wild man, probably reeking of earth and cattle. A man seemingly from nowhere, claiming the clouds would turn off on his word.

Of course they let him leave! They probably did so with not a little laughter to send him on his way. There was certainly no urgency to consider what he said, so they likely treated him like a man worthy of scorn.

We would have done the same.

This is a familiar scriptural theme. God’s messengers rarely arrive with polished résumés or impressive letters of recommendation, signed by the kind of names that have resale value. No, they don’t have the kind of pedigree that opens doors. Did they not say of the Master, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”

And yet, the biblical pattern is, as Paul observed, that God uses the things the world calls foolish to confound the wise (1 Corinthians 1:27). Elijah is no exception.

His name, Eliyahu, is a proclamation: “My God is Yahweh.” Not Baal. Not Asherah. The man is a walking sermon.

And his message comes with three points — a preacher if ever there was one — each one as countercultural as the man himself:

The Lord, the God of Israel, lives.

Before him I stand.

There will be no rain… except by my word.

Let’s take them in turn.

The God of Israel Lives!

“As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.”

Living as if God were dead may be our favorite national pastime. We wouldn’t profess this openly; polls still show that the vast majority of Americans believe in God. Every Sunday, churches welcome new members on public professions of faith. We stand and recite creeds together: “We believe in God the Father, Maker of heaven and earth…”

And yet, for all our talk, our lives tell a different story. After all, if words were all that mattered, you might conclude we were a nation of saints. But watch what we do, and the reality becomes harder to ignore: we are, as David Watson often calls it, “functional atheists.”

That is, we profess belief in God, but when it comes time to act, we trust ourselves.

This isn’t new. Ours is simply a modern version of an ancient problem. The story of Ahab shows how easy it is to keep God’s name on your lips while removing him from your life. For all their idolatry, the Israelites were still known as God’s people. But if you watched what they did, saw where they worshiped, a different story would’ve been told. As Elijah looked around the palace, he would’ve seen what Paul was disgusted by as he stood in Athens — idols everywhere!

Not only that, under the leadership of his tyrannical wife Jezebel, all of his policies honored Baal. He had priests and prophets, but they were yes-men for the gods of Canaan. Ahab believed in God — he just didn’t think God was relevant anymore.

And while none of us would want it said of us, “He walked in the ways of Ahab,” the path he paved feels all too familiar.

We pray, but mostly when things fall apart, rarely before.

We call on God in the hospital room, but ignore him in boardrooms.

We ask him to bless what we’ve already decided to do. He’s not our Lord — more like an emergency life raft.

A pastor once told a story of a woman whose husband he visited in the hospital. As he was leaving, he saw her in the hallway and said, “Let’s pray.” She looked at him, shocked, and said, “Do you think it’s that bad?”

A God we only approach when it’s that bad is not one we actually trust.

And yet, God listens. He honors even desperate, last-minute prayers from those who live as if he isn’t there.

Even so, faith was never meant to be relegated to the emergencies of life, and God’s presence cannot be confined to the catastrophes. As Brother Lawrence would discover and write about, God is present everywhere and every time. Not just in hospitals, but in homes. Not just in suffering, but in the mundane repetition of daily life.

To live as if God lives means trusting he is always near, and having all of your actions flow from the reality of his presence. This is what Elijah models for us; it’s why he is there in the first place.

He didn’t just believe God existed in some abstract sense. He believed God was active, personal, attentive, and that faith energized his life and commanded his attention.

That’s why Elijah doesn’t begin with a threat or a rebuke. He begins with reality: “The Lord, the God of Israel, lives…” It’s not just a theological claim; it’s a confrontation. One that stands against Ahab’s hollow religion, against Israel’s moral drift, and against our own functional atheism.

God is not an idea. He is not a mascot. He is not a backup plan. He lives. And if he lives, then he reigns. And if he reigns, then everything matters. Every thought, every action, every motive. Faith is not about remembering God abstractly or when it’s bad, it’s about living as if he’s present even when everything feels normal.

I Stand Before Him

Some topics stir a deeper hunger in people than others. In my 15 years of pastoral ministry, few generate as much curiosity as angels. I’ve received emails, invitations to coffee, and requests for classes — all from people wanting to know more about these radiant messengers of God.

It’s easy to see why. Angels are powerful beings. In Scripture, they appear as messengers, warriors, deliverers. They are creatures of immense beauty, strength, and wisdom. In many ways, they embody what we hope to become.

But such qualities can blind us. We can be so taken by what they are, we rarely stop to ask how they became that way.

When Gabriel visits Zechariah in Luke 1, he brings a message almost too good to believe: “Your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son…” Zechariah, trained by years of disappointment, replies, “How shall I know this? For I am an old man, and my wife is advanced in years” (Luke 1:18).

It’s a reasonable question. But Gabriel’s answer reveals what makes him who he is.

“I am Gabriel,” he said. “I stand in the presence of God” (Luke 1:19).

He doesn’t appeal to rank or résumé. He doesn’t remind Zechariah that he’s an angel or list the missions he’s completed. He points only to the One in whose presence he lives. That’s what’s important about him.

This is the open secret of angels. Their wisdom and power doesn’t come from themselves. It comes from where they stand.

Gabriel stands in the presence of God. So did the angelic hosts in Daniel’s vision (Daniel 7:10), the seven angels of Revelation (Rev. 8:2), and the beings surrounding God’s throne in Isaiah, Ezekiel and Revelation. Their lives are oriented around his presence.

If we truly admire them, we won’t just study them — we’ll imitate them. We’ll seek to live as they do, standing in God’s presence.

This, too, was Elijah’s secret. Before he stood before Ahab, he stood before God. That’s what gave his voice its weight and what gave him a steady courage. He didn’t act on impulse or opinion — bolstering himself with a type of practiced self-sufficiency as he approached Ahab’s palace. He acted from his place of standing.

“As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand…”

In the old films with kings and castles, the throne room was rarely empty. If the king was in residence, so were his servants. They stood there attentive, awaiting the smallest indication that it was time to serve. To stand before a king meant you were in relationship with him. It meant you were ready to serve. It meant you had authority to act in his name.

To stand before God is even more than that. Krummacher says,

I stand before the Lord, when I desire, above all things, that the will of the Lord may be at all times plainly manifested to me, and that I may do nothing, from one moment to another, but what shall please him, and promote his glory; when I keep my eyes waking, and place myself as it were at my post, to watch for the tokens of my King, and listen attentively with my spirit to his voice, and his commands within me and without; when I desire, according to the least of his intimations, to run the way of his commandments; I then stand before the Lord.

But this kind of attentiveness doesn’t happen automatically. Only those who see God as he truly is — as revealed in Scripture — will stand like that.

If we imagine God as a cruel taskmaster or a cosmic vending machine, we will only approach him in crisis, or when we want something. But if we come to know him as good and generous, merciful and just, and the essence of love, we will gladly stand before him always.

That was Elijah’s confidence. Like Gabriel, he didn’t speak from self-importance or self-reliance. His boldness didn’t come from a résumé — it came from a relationship. He was aware of the living God. Aware of his nearness, his power, and his goodness. And from that place of standing, Elijah could speak with simplicity, trusting that the One before whom he stood would empower the words he would speak.

No Rain, Until I Say So

Action is never optional. To stand in the presence of the living God is to be drawn into his work. Sooner or later, those who stand before him are sent by him to act in his name.

Thus, Elijah concludes his remarks with a staggering claim:

“As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.”

Not God’s word. My word.

It’s a startling phrase — “except by my word.” Not, “Thus says the Lord.” Not even, “The Lord has spoken,” but my word.

We wince a little when we hear it, maybe because we’ve seen too many self-made prophets prop themselves up in the name of God, using divine authority for human schemes.

But Elijah isn’t grabbing power, he’s been entrusted with it. And when he speaks, he’s not twisting God’s will to fit his own; he’s speaking as one whose will has already been shaped in the fire of God’s presence. What God wants, Elijah wants. What God is doing, Elijah does.

The New Testament gives us the clearest picture of this kind of union. In John’s Gospel, Jesus — once again — finds himself under scrutiny from the experts, this time for healing on the Sabbath. His response is simple and staggering:

“Truly, truly, I say to you, the Son can do nothing of his own accord, but only what he sees the Father doing. For whatever the Father does, that the Son does likewise” (John 5:19).

Elijah’s “my word” is a foreshadowing of what we see clearly in Jesus. When a life is surrendered, God’s will and ours begin to move in step. The voice that comes from that kind of life isn’t a proud one, but a properly tuned one. Like music, it harmonizes with the lead singer.

But there’s risk in this kind of obedience. Elijah’s words reflect a deep intimacy with God; yes, but they also expose him. Not to God, but to the world. Faith always looks foolish before it looks faithful. And just before we speak, fear creeps in, dressed up like wisdom, whispering: “But what if it rains?”

I once heard about a small country town caught in a drought — not because of sin, just bad weather. A few folks, half-joking, asked the local pastor to pray “to the big man upstairs” for rain. He said he would. But instead of offering a quiet solo prayer, he announced a special Sunday evening service outdoors.

When the time came, the people showed up in lawn chairs and Sunday clothes. The pastor walked out, scanned the crowd in silence, and then said, “Y’all can go home.”

Confused, someone asked, “Why?”

He said, “We’re here to ask God for rain, but nobody brought an umbrella.”

Faith doesn’t just ask — it prepares, it ventures on God to do what he promised.

That’s what Elijah did. He didn’t just pray for the rain to stop. He stood before a king and said it would. In doing so, his reputation, his safety, his sanity — all of it was on the line. Because that’s what faith does. It speaks in tune with God, despite current conditions.

This is a terrifying reality for many of us, but the Bible is full of people who’ve walked this path.

Once, Jesus was teaching in a crowded house. Four friends tore through the roof to lower a paralyzed man before him. Jesus saw their faith and said to the man, “Son, your sins are forgiven.”

Some experts scoffed, “Who can forgive sins but God alone?”

Jesus, knowing their thoughts, answered:

“Which is easier, to say to the paralytic, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Rise, take up your bed and walk’? But that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins’ — he said to the paralytic — ‘I say to you, rise, pick up your bed, and go home’” (Mark 2:8-11).

And he did.

When someone lives as one who stands in God’s presence, they will eventually be called to put themselves on the line, just as Jesus did. There is no way around it. Faith always requires skin in the game. Without risk, it isn’t faith at all. And as the writer of Hebrews reminds us, “Without faith it is impossible to please God” (Hebrews 11:6).

Dallas Willard once said, “The cautious faith that never saws off the limb on which it is sitting never learns that unattached limbs may find strange, unaccountable ways of not falling.”

Elijah sawed at the limb. He took the risk. He announced the drought before it happened.

This is how faith — trust, really is a better word — grows. By acting, not recklessly, but in response to a word that comes from the Presence.

Peter learned this, too. While going to prayer one morning, he and John were accosted by a disabled man, begging for silver or gold. Peter — expressing one of the downsides of ministry — said to the man, “I have no silver or gold.”

But he didn’t stop there, for he did have something he could give. Something that came from standing on the solid rock that is Jesus Christ. He continued, “But what I do have I give to you. In the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, rise up and walk!”

What he does next is instructive — it is putting his faith on the line. “He took him by the right hand and raised him up, and immediately his feet and ankles were made strong” (Acts 3:6-7).

Something happened when Peter reached for the man’s hand. God’s power was present to bring about the very things Peter did on behalf of Christ.

He didn’t wait to see if the man twitched. He reached out, grabbed his hand, and pulled. And as he pulled, God’s healing power flowed into the man’s body.

“Immediately his feet and ankles were made strong” (Acts 3:7).

God’s power flowed because Peter acted.

“Faith without works is dead,” says James.

Missionary Hudson Taylor once said, “All giants have been weak men who did great things for God because they reckoned on his power and presence to be with them.”

Because they reckoned, they acted. Elijah reckoned, and he spoke. And because he spoke, God acted.

It did not rain until he — Elijah — said it would.

Mock First, Mourn Later

Did they believe him?

Of course not. That he walked out of the palace is proof enough. The king probably forgot his name by the morning, probably chuckling at the memory of that wild-eyed, dusty lunatic that wandered in, claiming to have power over the weather.

George Bernard Shaw once said, “All great truths begin as blasphemies.” Swap blasphemies for crazy ideas, and I’d agree with him. So would Ahab.

Then the skies shut off. The crops shriveled. And the laughter faded into anger.

The word of the one who stood before God was no longer so easy to dismiss.

Here’s a brief accompanying YouTube video.

Peace and Goodness!

This message is truly inspirational! It relates to your last series about spiritual senses. Elijah demonstrates his spiritual senses (by declaring there will be no rain) only because he stands before God. And then Ahab is an example of having no spiritual senses. I pray my faith and spiritual senses will grow. Thanks for this wonderfully encouraging message. God bless! 🙏🏽

Funny we both wrote about presence within the same week! God's trying to get a message out there for sure